OBSERVATION: A House on The hills of Hermel - A house as Landscape

The vernacular of juniper, stone and gorse hills

On Hermel’s foothills, a group of houses emerge, forming a material collage of the surrounding landscape.

Often within a landscape, houses tend to stand out as foreign objects, the shape and materiality in contrast with the surrounding nature; such was not the case in the context of the hills of Hermel.

The houses, called ‘khymat’ (meaning tents, and the singular form 'khaimeh'), revealed themselves as another version of the landscape, built solely out of locally available materials: stones, branches, tree bark and live gorse-type plants, called Kebkab, sheltered by the canopy of the ancient juniper trees.

Looking down onto the valley with a cherry orchard. The green dots of the mature juniper trees continue towards the horison.

Juniper trees are extremely slow growing and only sprout out of seeds digested by birds, mature trees reach the age of 4000 years and provide shelter from the wind, snow and sun in an exposed site of Mt. Hermel.

Until about 50 years ago, about 20 such dwellings formed a scattered hamlet. People grew wheat, oats as well as vegetables and fruit trees. The habitation was seasonal; in spring, grazing the livestock and planting wheat and oat leading up to autumn harvest season, and in the winter, people would migrate lower down to the immediate valley to take refuge from the heavy snow.

In the book, “Dwellings in the Bekaa”, Houda Kassatly describes the use of Khymat as below:

”The Bekaa's sheperds have a special structure called 'khaimeh', or tent, which serves to place goatskin recipients for cheese and other products of rearing. In the region of Aayoun Orghouch, these structures are made of mud. In the Hermel however, their proportions are much larger; placed against the houses, they are made of stone, and their rooftops of reed and brushwood.” (p.77 Kassatly, Houda. Dwellings in the Bekaa: Design of rural housing on the Lebanese Plateau. Paris, Geuthner. 2000)

Around 10 Khymat remain currently, some in ruin, others in active use. One family stays on site as the custodian of the Juniper trees and look after the land.

TREE LOCATION DICTATES THE HOUSE LOCATION

As such, Khymat hug the juniper tree in various configurations, some central, some to the side depending on the number of rooms and orientation. The arrangement and the number of rooms are indicative of the size of the livestock, family structure of each household and the character of each juniper tree.

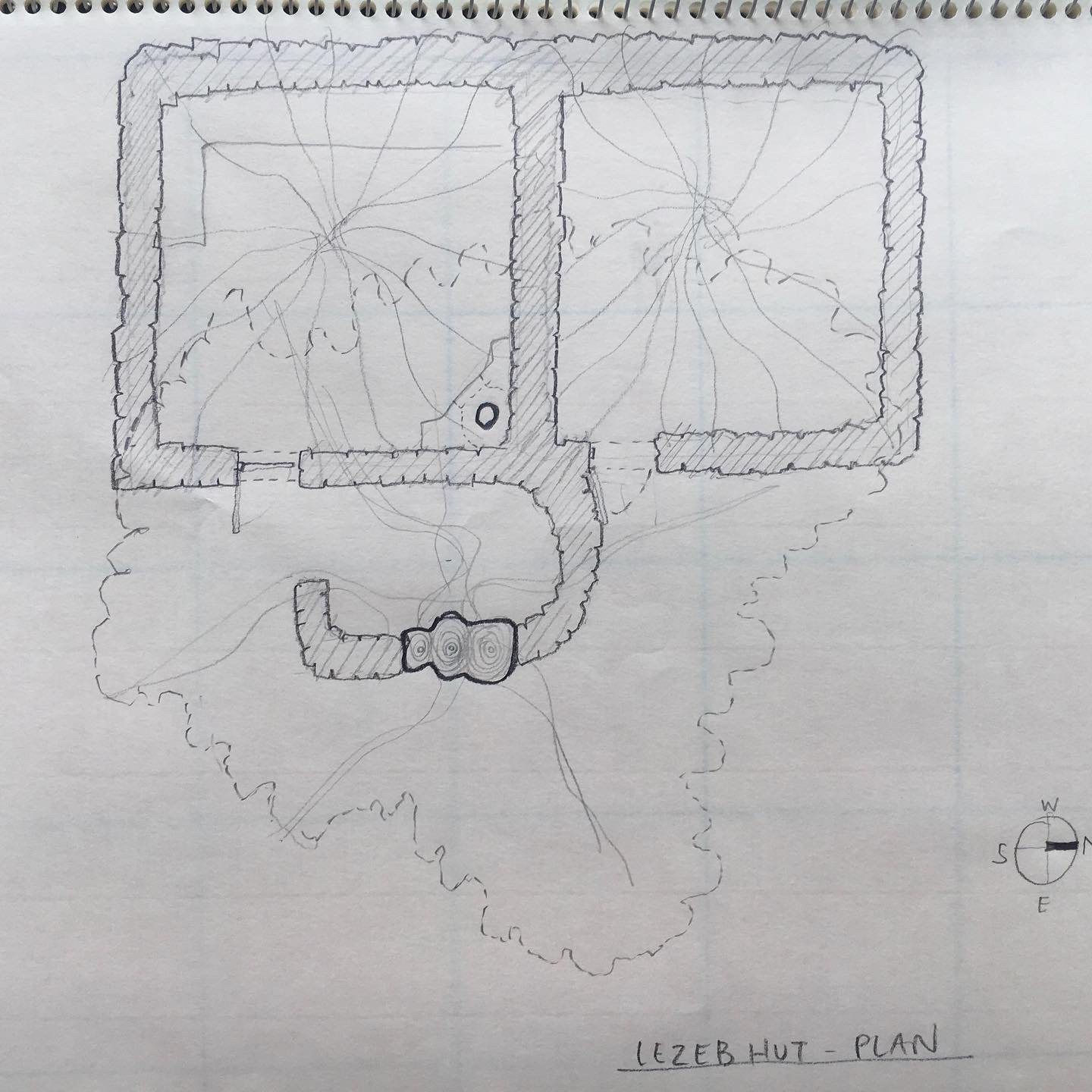

Plan oriented N-S, Eastern aspect protected under the juniper tree canopy, minimising heat gain from morning sun.

Plan layout with a juniper tree at centre well protected all around with the tree canopy: half-crescent shaped low stone wall forms a pen for the livestock.

Two rooms with a small pen at front: One of the rooms has a wood-burning cob stove at the corner. Interior of the stone wall is rendered with clay-sand-straw base coat with lime rendered top coat.

ROOF TYPOLOGY

The most commonly typical vernacular roof of the surrounding Beqaa Valley is a flat roof. Built out of timber rafters lined with a reed mat with compacted sand/straw/clay roof, the final water-proofing layer is topped with a rolled lime rendered finish. The flat area of the roof provides working space for agricultural processing: drying and processing of grains, fruits and vegetables.

Unlike the commonly typical flat roof design, Khymat houses in the hills of Hermel are formed with a cone-shaped pitched roof, perhaps reflective of the remote nature of the location where access to timber, reeds and lime is limited. The cone-shaped roof is built from found branches loosely arranged to form a single peak. Piles of tree bark and Kebkab (live gorse-type bush plants) are laid to provide enough thickness to act as waterproofing above. The pitched roof helps shed the heavy winter snow and autumn-spring rain. The spiky structure of Kebkab plant naturally binds itself to form a thatch-like uniform roof.

Interior of the house with a cob built wood burning stove at corner. Roof framing built out of found tree branches tied at centre.

An image of a kebkab plant (a gorse-type bush plant) surviving the dry spell and the harsh summer sun.

The pitched Kebkab roof is easily repairable (literally, by picking up another plant off the surrounding landscape and placing it back on the roof), in contrast to the commonly typical vernacular flat roof form, which needs to be maintained periodically by rolling a large stone cylinder over the roof to re-waterproof through compaction.

Symptomatic of the cement-based resource infrastructural shift that proliferated in the 20th century, the majority of traditional lime-rendered flat roofs have been replaced with cement roofs. In contrast to the flat roofs, which have gone through the material shift from lime to cement, the material status of the remaining Khymat houses in Hermel is relatively unchanged.

The simplicity of hyper-local material sourcing and the ease of maintenance of the Kebkab plant roof stood the test of time, rather, evaded the drastic material changes imposed by modernisation, playing a significant factor contributing to its longevity.

A picture of the stone cylinder roller: a maintenance tool for compacting lime flat roof.

The wooden lintel was the only material that had weathered and shown the passing of time.

Unassumingly inviting entrance.